Artist Development Blog #1: On Collaboration

BEST PRACTICES FOR COLLABORATION IN FILM & TV

Producing film & television is collaborative. Unless you’re making experimental video art or short videos online, it is extremely difficult to tell a complex story all by yourself.

Collaboration is one of the hardest things humans can do. In production, everyone needs to have a say but ultimately only a few people make the key decisions. There’s almost always some power imbalance or hierarchy in collaboration.

Over the years I have noticed the most common conflicts in the OTV community involved the challenges of collaborating.

I’ve been tracking these issues and offer this blog to give advice on how to avoid the common pitfalls in collaborating to make film & TV in the indie space.

I offer advice based on how I am perceiving the world today, my understanding of history and my dreams for the future. Some of this advice offers solutions that I believe should be the future. Some advice is just to help folks survive this capitalist system. These parts will focus on how things work in the corporate world, because many of the people I have observed have dreams of Hollywood. In general, I believe the Hollywood system is broken, even though it’s trying to do better. Still, it’s what many artists have to navigate in the present moment if they want to make a living as an artist in film and television. My goal is to offer what I’ve learned to help us navigate it better as a community.

CULTIVATE PATIENCE + HUMILITY

Patience is critical to collaboration. Take your time. Everyone needs time to process.

There is a saying that the dominant style of film/TV production is “hurry up and wait.” It’s definitely true on set, where specific crew members may have nothing to do for hours but then must do their job quickly to keep things moving. It’s even true in post-production, which can take months or even years but can speed up with interest from a distributor or festival. Even after the project is completed, the process of pitching larger stakeholders can move at a glacial pace, before someone important gets interested and then things move fast (and then...expect more delays). Because of this, reminding yourself that “there is time,” that not everything will go according to plan so changes will have to be made on the fly, will mentally prepare you to give yourself time to process and ride the waves as they come.

Humility is about understanding that everyone hears, thinks and moves differently, and that we are learning and changing all the time, so the pace of your project will ebb and flow. Pride will kill collaboration because it privileges one person’s feelings over another’s in a process where everyone needs to feel seen and heard.

A loving, patient, humble communication style will avoid many of the small hurts that add up to big problems that will cost you time, money and productivity.

WORK WITH WHO YOU KNOW AND TRUST

Trust is critical in collaboration. Without trust, tasks take longer and face more obstacles.

Work with people you know and trust, or people recommended by people you know and trust. The longer you’ve known someone, the better they can communicate with you in high stress situations, or the better they can recommend someone who compliments how you communicate under pressure.

It is hard to only work with people you know. A lot of roles need to be filled, and, especially if you’re just starting out, you won’t know everyone you need. For emerging storytellers, given the option between an advanced professional who you don’t know and an amateur/emerging professional you do know, you may get a better product with the person who is less experienced but trustworthy. That said, I’ve seen people work with crew they didn’t know and created a great product, but the experience in production was quite challenging.

Even if you are friends or comfortable with your collaborators, you should treat the production as a professional endeavor. This means defining roles and responsibilities as clearly as possible, including signing clear contracts!

Photo credit - Nuccio DiNuzzo

DEFINE ROLES & SIGN CONTRACTS

Roles help your collaborators understand what they have to do, how much power they have in particular situations or conversations, and which skills are more useful to the project.

The challenge with defining roles in the indie space is that creators often won’t have enough money to fill all the necessary roles. Some members of the crew may end up doing things outside of their immediate job description out of necessity. This is often unavoidable, but if people are stepping out of their role, everyone should be aware that that is what’s happening. Even just acknowledging that it’s happening can make someone feel better and diffuse conflict. It is also important to note when determining credit or compensation.

It is best when everyone is honest about their strengths and weaknesses in particular roles. For example, when I directed my first short, I was aware that I was new to it and would need to learn. My cinematographer ended up doing some on-the-spot directing, naturally compensating for me. Because I was honest about my weaknesses, I could take this advice in stride instead of feeling threatened that they were “usurping my authority.” Having the humility to know what I don’t know was critical to creating a healthy production environment.

Everyone on set should be under contract. Contracts help define roles, ownership and methods of payment. If you are working with OTV, we can provide you with contract templates.

CO-WRITING IS HARD. SIGN A COLLABORATION AGREEMENT!

In the indie TV space, the most important role to define is the creator, who is the “intellectual property holder.” Traditionally in TV this is the writer and in film it is the director. If there is more than one writer (especially) or more than one director (more rare), you will need to sign a collaboration agreement!

It is important to define who “owns” the project. At OTV we now provide creators with collaboration agreements if there is more than one intellectual property holder. This agreement specifies that multiple people share intellectual property interest and how much they own, sometimes specifying creative ownership (characters, trademarks, setting, etc.) and formats (separated rights to adaptations, books, films, sequels, etc.).

This agreement is separate from ones you might have with investors or other entities to support production; it is often good practice to give key investors or stakeholders a promise of some percentage of sales, though it can be tricky, especially in TV, to deliver on that promise.

Be careful who you decide to share intellectual property with. It should be someone you trust with your life. Once signed, a collaboration agreement will bind you to them for the life of the project. If you are planning to continue developing the project into something bigger -- selling to a big studio or network -- these agreements will help define who has a say in the story and how much they will benefit from the deal. You may not be able to cut them out. If a studio sees there is disagreement on who owns the series, it could kill the deal. No corporation wants to be sued because the “chain of title” or ownership is unclear, even if you propose changing the title, story or characters so it’s a different form of intellectual property.

When a corporation buys a project, it typically only wants to deal with one or two intellectual property holders. They will buy out any investors. Your crew, who are typically contracted as “work for hire,” will not be guaranteed to work on the project moving forward, even if they are in the appropriate union or guild (if they are not, it’s even harder to keep them involved). If you’re writing a series, do not promise your director of photography or cast that they will work on the show if WarnerMedia or Netflix buys it for development.

Understanding that the writer often has the most power in TV and the director in film is critical for every artist to know. I often see actors work with friends to write scripts for them; they have stories but don’t want to do the actual scripting. This is dangerous for a number of reasons. The non-writer is ceding power to the writer. Ownership of the project becomes blurred in ways that make creative decisions on the indie level difficult and make future development of the project very tricky, because corporations will see the writer as the owner not the creator-actor.

The easiest way to control your story is to write it yourself. Writing, in my opinion, should never be outsourced or “work for hire” (unless in those rare cases, e.g. when ghostwriters are being paid above scale to complete books for celebrities). While I love collaboration, I often think writing is one aspect that is best done solo in the indie space, especially for indie TV series angling for bigger deals in Hollywood (it’s different at the corporate-level where the Writers Guild has very clear rules on credits).

UNDERSTAND CULTURAL/POWER DIFFERENCES

The biggest problems I see in collaboration fall along cultural lines. It’s been heartbreaking to see, but most collaborations I have seen between people of color and white people -- usually between co-creators, between creators and directors/DPs or between creators and producers -- do not last. I wish this wasn’t true, but there’s too much evidence to avoid it. I’ve noticed this at least a dozen times over my four years running OTV.

The specific reasons why POCs and white people struggle to collaborate is different every time. Often the question is about power and control, though sometimes the issues are complex and interpersonal -- for those who are fans of astrology, you know: sometimes personalities just don’t match!

Different levels of experience among POCs and white can bring out triggers. Often, the white person is more experienced in film (the industry is historically white for lots of reasons) and the POC feels “talked down to.” This feeling of being inadequate is amplified during the high-pressure environment of production, where time is money and every second wasted brings changes and compromises to the story. The feeling of marginalization can be particularly acute when it’s the POC’s own story. It is important to white people in production to understand the position of their privilege when working with people of color, learn when to stop talking and when to communicate with patience and humility, particularly when POCs are the creators and storytellers. Storytelling can be incredibly vulnerable and creators need care in the process, even if you’re on set and running behind schedule.

At the same time, people of color need to own their power in production. If the story is yours, then your voice matters more. I have seen producers of color get sidelined by white creators. I have seen people of color have white people write their stories, only to be dissatisfied with the authenticity of the project. I have seen people of color sign contracts that give executive producers complete control over the project, when they as the writer should be able to decide who the show sells to and who gets to profit. I have seen people of color partner with production companies that offer no support services, leaving all the fundraising and pre-production work to the POC creator while the company takes credit for doing much less work.

Conflicts can fall along other lines as well: cisgender vs. transgender, queer vs. straight, and differences in class, nationality, disability and even religion can amplify conflicts. Here it is important we understand what Patricia Hill Collins calls the “matrix of domination.” Everyone experiences oppression differently depending on how they identify, a matrix of oppressions and privileges. What feels oppressive to someone may not to another person with the same identity. But people who are privileged -- and most of us have some privilege -- need to acknowledge that their identity may be amplifying conflict and “sit down” or “step back” to allow the other person who may not have those privileges some time to process their feelings. As a Black queer cis-identified person, I have had several moments where I needed to stop being defensive and let women, trans and nonbinary people of color express harsh truths or anger at me, even if sometimes I didn’t, in my view, do anything wrong. If I have done or said something wrong, I’ve learned more about myself and my collaborators, making myself and the project better (only after apologizing and taking steps to restoration!). Sometimes, the people mad at me have often acknowledged that I wasn’t the problem and they were merely triggered because someone with my identity or who they associate with me had hurt them in the past or is hurting them now. It may take months for people to process where the hurt comes from, and that’s OK.

So all of my previous advice still stands. No matter your identity, you should have the humility to consider that you may be wrong or not have all the information. Ask questions when something is unclear. It’s OK to not understand, but reacting out of hurt pride will only cause more harm. Don’t be intimidated if you need something explained to you. And if it’s you who has to do the explaining because it’s a matter of experience, do so with as much care and humility as possible, especially if you are in a culturally privileged position.

INTEGRATE BRAVERY & HEALING INTO YOUR PRODUCTION PLAN

The film/TV industry is waking up to the rampant toxicity across the business, and new roles are emerging to manage it. From intimacy coordinators to inclusion riders, the industry is reckoning with how to develop new systems and make production empowering for all.

Some ways of integrating healing into your production plan:

Everyone involved should introduce themselves as humans first and professionals second, every day or at every location. This includes cast, crew, community members, location hosts, etc. Everyone should learn names/pronouns and have an opportunity to discuss the contributions, gifts and intentions they are bringing to the space.

Start every day of production with meditation or grounding exercise/check-in.

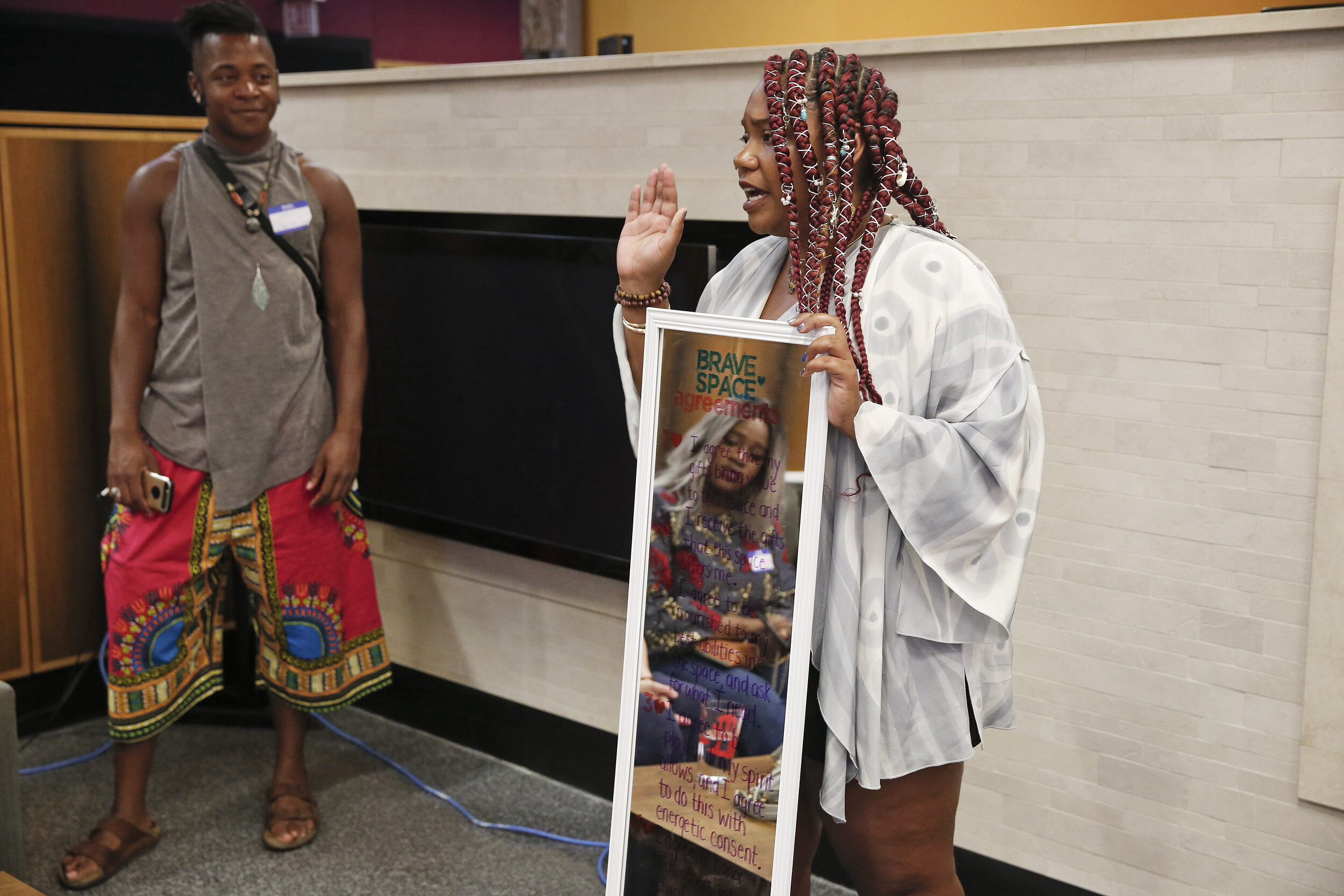

Set Brave Space Agreements with crew, cast and key stakeholders. Make it editable (marker on dry-erase board or glass) and constantly revisited or displayed.

Always provide healthy food on set and in every meeting. Make sure you know everyone’s dietary preferences. If you cannot afford to feed people well, you cannot afford to be in production and need to raise more money or call in more favors!

Take breaks and avoid going over schedule (any day that is over eight hours).

Make space on set for people to pull away. OTV’s former head of community Jenna Anast recommends a “peace corner” or “peace room,” a place on set where anyone can be alone and process feelings without being disturbed. Other methods like lighting incense or creating altars can help set a relaxing and grounded tone.

If you have intimate/sex scenes, hire an intimacy coordinator. Someone neutral, other than the director, should work with talent to ensure their boundaries are respected.

Budget for conflict resolution/mediation. Conflict resolution is a skill, one best done by neutral parties and increasingly a service consultants offering to media makers. Having a mediator on hand to visit the set or mediate conflict pre- or post-production is an expensive but responsible way to ensure your collaboration doesn’t dissolve simply due to poor communication. OTV has connections to restorative justice consultants and facilitators who are familiar with the TV/film production process. Please reach out to us if you find yourself in need! Healing is at the center of what we do because art is healing so the process of making it should be as well!

Photo credit - Nuccio DiNuzzo

IN CONCLUSION

Film/TV production is troubleshooting. Conflict is inevitable in production and not everything will go according to plan.

You should embark on production expecting conflict and emotionally preparing yourself to be vulnerable enough to ask for what you need, even if just a few minutes to process your feelings.

The production process benefits from clarity, patience and humility. The toxic trope of the fascistic director or producer does not have to be. We can tell our stories without the process leaving us worse off than when we started.

We’re all in this together.